Mountain Town: Tom

Part One

By Ivory Harlow

April, 1986

Mountain Town High School gym transformed into an electronic disco, complete with a black-and-white checkered dance floor, neon lights and disco balls. Slow ballads dominated the playlist as prom came to a close. Tom and Jackie swayed side to side to Take My Breath Away from the hit movie Top Gun.

Tom was a senior and Jackie a junior. He promised her he’d come back to take his longtime girlfriend to her senior prom, next year, even though he would graduate in just over a month. Tom’s friends told him it’d be lame to go to a school dance after graduation, they called him ‘whipped’, but he didn’t care. He would do anything to make her smile.

Thomas Saunders was bit by the love bug three years earlier, when Jaqueline Lawry walked into the first day of study hall. An oversized purple sweatshirt hung off one shoulder, making her tiny 5’3” frame look even smaller. Her blonde ponytail bounced with every step. During roll call he abandoned the table of his friends, leaning lazily back in their chairs cracking jokes, to sit opposite his love interest. She had a stack textbooks, trapper keeper, and new ink pens in front of her as if she actually planned on doing work in study hall, but now, facing all 6’3” of Tom’s boy-man angled awkwardly to fit between two classmates at the school lunch table, her lavender gray eyes met his cool blue ones, and she smiled.

“You look beautiful,” he said, pulling Jackie flush against him. She wore a strapless purple taffeta dress with a matching headband, her three-inch heels brought the top of her head to Tom’s chin. He tucked her under it.

“You should wear this dress when we get married,” he told her.

“I can’t wear purple at our wedding Tom, I have to wear white. It’s tradition!” she poked his ribs.

Parents told them they were too young. Teachers told them they had a wide world of opportunities. Even their friends thought they should see other people before settling down. But Thomas and Jacqueline knew that this was it. They were meant for one another.

When the song ended, Jackie let her arms drop from around Tom’s neck. Her expression turned serious. “Let’s go,” she said, grabbing his hand and leading him towards the red EXIT sign. “I have something to tell you.”

Tom parked at the back of the high school lot, where he and the other redneck kids parked their trucks on school days. He was from a working class family and looked and acted every bit. Jackie was an only child. Her father was President of Mountain Town Bank and her mother was what his people called a ‘kept’ woman, meaning she managed the house and family’s social calendar. Tom worried he wasn’t good enough when he first asked her out, and later when she introduced him to her parents. But she beamed with pride whenever she was with him- holding his hand in the hallway at school, riding shotgun around Mountain Town in his old truck, or dropping off a bag lunch at his job at the quarry.

“Are you hungry?” Tom asked as he opened her door and helped her inside.

“No. But you are,” she giggled. Tom’s teenage appetite, physical job, and towering stature meant he could really pack away the food.

“How about a chocolate shake from Carl’s?” he suggested. “You sip on it while I eat enough for both of us?”

Jackie rolled her eyes.

Carl’s Diner was a 1950s style metal building in downtown Mountain Town. It was the only place open 24 hours.

They sat across from one another in a red vinyl booth. Tom ordered, then turned his attention to Jackie. “What did you want to tell me?” He asked after taking a long drink of his sweet tea.

Jackie’s face fell. She looked around the restaurant. At this time of night/early morning, there were only a few booths occupied by long-haul truckers and people leaving the bar after the last call. She began to tear up.

“Hey…” Tom got up and rounded the booth to sit next to her. He put his arm around Jackie and pulled her to him. “What’s wrong?”

Tom was totally confused. They had a great time at prom, took dozens of pictures, danced the night away with their friends.

“I’m pregnant,” she whispered into his shoulder.

He wasn’t sure he heard her right. “You’re pregnant?” he asked, pulling back slightly to look into her eyes.

When she nodded, the tears brimming her eyes spilled down her cheeks.

When they started going steady, Jackie was adamant she would not have sex until marriage. Tom didn’t convince her otherwise. ‘Good’ girls like Jacqueline Lawry did not sleep around. Also, he was going to be the one to marry her; as much as he wanted to have sex with her sooner rather than later, he would wait if that’s what she wanted.

They’d been going steady for a while when things got hot and heavy in his truck. He held back to respect her boundaries, but she told him she’d changed her mind. Since then, they snuck around whenever they could. They were safe about it, most of the time... Though Jackie’s pregnancy was a surprise, it wasn’t like he didn’t know it could happen.

He brought her face to his for a kiss, then wiped her mascara streaked cheeks with his sleeve. “So it’s sooner than we wanted. Not a big deal. I’m going full time at the quarry when I graduate. We’ll find a place to rent in town until we can afford a house…”

“I know you’re disappointed you won’t graduate with your friends, but a GED is the same thing as a diploma. You can finish from home while I watch the baby at night.” Tom described the image his mind conjured: Him holding their swaddled baby while Jackie took notes at their kitchen table. Tom didn’t think it was possible to love her more, but knowing his baby was in her belly made his heart swell.

He continued, “You always said you wanted to have a big family. So what if we get an early start?” Not only was he confident he could take care of them, he was determined to convince Jackie the same. “I promise you, Jackie.”

Jackie stared blankly at the vinyl table, the pile of napkins she’d been shredding as he talked. After a moment of silence she looked up into his eyes, so full of love for her, for them, and said, “You don’t understand Tom. We can’t keep the baby.”

II.

Jackie didn’t answer Tom’s calls the Sunday after prom. She wasn’t at school on Monday morning. That night, Tom called her house and left two messages. She didn’t return them.

Tuesday after school, Tom drove to her house before B shift at the quarry. The Lawry’s housekeeper Dolores apologetically told Tom she’d tell Jacqueline he stopped by to see her.

Wednesday came and went.

Jakie told him that her parents prohibited them from keeping the baby. Tom worried the longer she was isolated from him and under their influence, the more she would believe that lie. He was running out of time.

Thursday morning he drove right past the high school to Mountain Town Bank. He sat in the lobby, wringing his ball cap, while he waited to speak with the President. He looked down at his worn Wranglers and dusty work boots and prayed he could convince his future father-in-law he was worthy.

“Thomas,” Mr. Lawry’s booming voice called Tom to attention.

Tom stood, “Sir. Can I speak with you in private, for a minute?”

Mr. Lawry scowled.

“I know you’re busy. I won’t take much of your time.”

“Very well. In my office.” He ushered Tom through the heavy mahogany door and closed it behind them.

“Sit,” he instructed, motioning at the green leather chairs facing his desk.

Tom sat.

Mr. Lawry perched in his executive chair, placed his hands on his desk, fingers intertwined.

Tom cleared his throat and said, “I know we are young. And that you and Mrs. Lawry love Jacqueline, and want what is best for her, but so do I.” Tom took a deep breath to steady his voice. “I don’t know the baby yet. But I love it too. I will take care of them, Sir…”

“And just how do you plan to do that?” Mr. Lawry cut him off.

“I’ve been working at the quarry for two years. I’ll go full time as soon as I graduate.”

Mr. Lawry leaned back in his big, leather chair. He gave Tom a condescending smile.

“How much do you make an hour?”

“$9.30 right now, but I’ll get a .50 cent raise when I’m full time.” Tom had thought he had a good job. He was making more than a lot of guys in their 20s, more than twice the minimum wage.

“You think you can support a family on $9.80 an hour?”

Tom’s face fell. “I’ll get a second job, a third job, if I have to- whatever it takes.”

Mr. Lawry laughed out loud. When he finished, he took off his glasses and set them on the desk. He looked Tom in the eyes. Tom’s face was flushed rage red.

“I did not intervene in Jacqueline’s little crush on you before now because I thought you were harmless. Then you went and knocked her up...” Mr. Lawry lowered his voice. “Go back to your side of the tracks Thomas and forget about her and the baby.”

Tom took a deep breath and stood to his full 6’3”, towering over Mr. Lawry’s desk. “Respectfully Sir, I will never ‘forget’ about Jackie and my baby. I made a promise and I’m gonna keep it!” Tom turned on his heel and stomped out of the office, leaving Mr. Lawry shaking his head.

Tom barely paused at the stop signs as he sped to the Lawry house. He whipped into the driveway and jogged across the immaculate landscaping to the front door. He lifted his hand to knock, but before he could, Mrs. Lawry opened it. She glared at him, hand-on-hip.

Under usual circumstances Tom would have tried to butter up Mrs. Lawry, despite her snootiness, but he’d already lost his bearing to Mr. Lawry’s shitty attitude. He couldn’t grin and bear her too. “I’m here to see Jackie,” he demanded.

“She’s already gone,” Mrs. Lawry said through pursed lips.

“What do you mean, ‘gone’?” Tom’s heart raced.

“Jacqueline went away,” Mrs. Lawry said coolly, “to resolve her unfortunate condition.”

Tom’s hand balled into fists at his side. He was too late. But it wasn’t too late for them. When she got back, they’d leave town. He’d get a job at a quarry in Colorado, or a ranch in Oklahoma.

“She won’t be back.” Mrs. Lawry seemed to read his mind. “Jacqueline will finish high school at a boarding facility.”

Tom felt frenzied. “Where?!” he shouted.

“Far away from Mountain Town,” was all Mrs. Lawry offered.

He staggered back, his entire world thrown off balance.

In a softened tone, she said, “It’s what’s best. For everyone.” Then closed the door in his face.

“It’s what’s best for YOU!” he shouted, “Not for HER! Not for the baby! Not for US!” He pounded his fists on the door, then kicked it, leaving a dusty footprint on display.

Tom sank to the concrete steps, buried his face in his hands, and cried until he was out of tears.

III. April, 2025, 39 years later

“Last calves of the season dropped today,” Tom called out as he rode his horse to the big house. Les Calder, patriarch of the Bar C Ranch, saw him coming and stepped out on the porch to receive him.

“Three healthy Angus and two black baldies, grazing in the upper pasture with their mamas,” Tom beamed.

Tom had served as Bar C Ranch’s Trail Boss for 30 years. First under Les’s direction, and now his son Post’s leadership. As trail boss, he oversaw 900 head of Angus, Hereford, and crossed cattle, commonly called black baldies, on 24,000 acres outside of Mountain Town.

Tom’s dedication and experience to the ranch allowed Post to focus on the Bar C’s horse breeding and training operation. Bar C performance horses attracted buyers from British Columbia, Canada, to large and wealth ranches in Chihuahua and Coahuila, Mexico.

Tom moved back to Mountain Town after eight years riding the rodeo circuit. He’d only intended to stay in his old hometown to recuperate. But he fell in love with the job he took cowboying at the Bar C and moved into the bunkhouse and never left.

Eight cowboys reported to him now, though they felt more like his sons than his employees. When his parents passed in the early 00s, the Calders and Bar C cowboys became his family.

“That’s quite a capstone to calving, and a great way to end the week,” Les said as he stood on the porch, buttoning his dress shirt sleeves. Tom noticed he’s traded his standard ranch clothes for fresh pressed blue jeans and polished boots.

Post emerged from the big house similarly dressed.

Despite Les being a decade older than Tom, Post was about the age Tom’s child would be. Tom imagined what his relationship with his child might have been, as he listened to the Calder men banter back and forth, work side-by-side.

“Where y’all headed?” Tom asked.

“Funeral wake,” Post said, dusting off his Stetson before setting it on his head. Chauncey, Post’s girlfriend and Bar C cowgirl stepped out the door next.

Tom whistled then tipped his hat. “You look pretty as a peach,” he offered a compliment. A paisley floral western shirt and jeans was as dressed up he’d ever seen her.

“Thank ya Tom!” she smiled. “I’m makin’ them take me for a shake afterwards, if their makin’ me sit through this funeral thing.”

Tom chuckled. He had always liked her blunt, down-to-earth, attitude.

“Who died?” Tom asked.

“Roger Lawry,” Post said nonchalantly.

“Mountain Town Bank President for 50 years,” Les added, unsure if Tom knew the man.

“Lawry was a son of a bitch, but a good banker. He gave the Bar C grace more than once over the years. Figured we’d pay our respects to the family.”

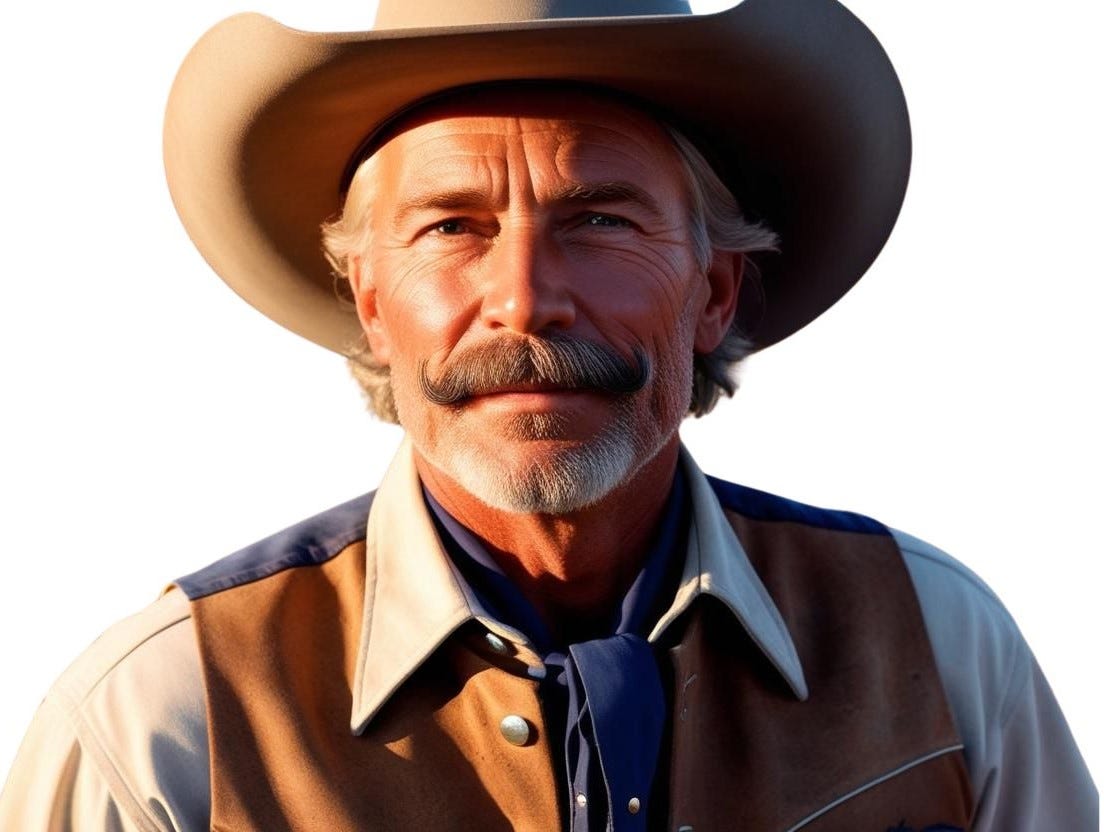

“That’s kind of y’all,” Tom said. His handlebar mustache, full beard, and cowboy hat helped to hide his facial expression which conveyed his true feelings about that man.

“The funeral is tomorrow afternoon, but we’re leaving for the Ranch Horse Clinic and Show in Bryan, Texas, first thing in the morning,” Post explained.

“I remember,” Tom nodded in acknowledgment. “Me and the ‘boys will hold things down here and we’ll see y’all next week.” Tom touched the brim of his Stetson, gave a mock salute and turned his horse towards the barn.

He gave his horse a good brushing, flake of hay, and fresh water, before turning in for the night. Instead of taking his supper in the bunkhouse kitchen with the ‘boys, he told them he needed to add the new calves’ birth weights and update livestock records, and took his plate to the ranch office in the next building over.

Tom scooped barbacoa into corn tortillas as he fired up the laptop. He typed ‘Roger Lawry’ and ‘Mountain Town’, ‘obituary’ into the search engine. The first result said:

It is with heavy hearts that we announce the passing of Roger Lawry, on April 7th, at age 85. He was a devoted banker and an active member of the Mountain Town community. He is survived by his wife and daughter Jacqueline Durran. The memorial service will be held on Saturday, April 10th at 1 p.m. at the Mountain Town Funeral Home. In lieu of flowers, the family requests donations to the American Association for Cancer Research.

Tom opened another tab and Googled ‘Jacqueline Durran’ and ‘Texas’ and there she was. He clicked to enlarge the Dallas Society Ladies' Luncheon photo. She wore a form fitting eggplant colored sleeveless dress that just covered her kneecap, and very high heels which boosted her petite frame to the height of the other ladies. Her blonde hair was styled in a sleek bob.

Tom leaned towards the screen. He had an optometry prescription for farsightedness, but he never filled it; he could count cows in far-off pastures just fine. Now he wished he would have so he could look into her lavender gray eyes again.

He sorted through the search results, stumbling upon a social media profile with a candid close-up of Jackie’s face. He thought he hit the jackpot, but when he tried to access the page, the site prompted a login.

Jesus Christ, not now! Tom fumbled, trying to find a way around the login pop-up, but it was no use. Frustrated, he stood up, ripped the laptop cord out of the wall, and cradled it in his arms as he ran to the bunkhouse.

“I need help!” he announced as he stomped through the door. It was Friday night, and the group of younger cowboys were gathered around a game of Texas Holdem’ at the kitchen table. Dozens of empty beer cans and bottles littered the only blank spot. Tom swiped them aside to make room for the laptop, then set it on the table facing them.

“I can’t get into MyFace or the pink camera one.”

The cowboys looked at one another confused. Jake snickered.

“Are you trying to use social media, old man?” Ryan asked with an air of loftiness.

“Yes,” he said unabashed. “Fuckers trying to make me log in to see shit.”

“Do you have a Facebook account?” Travis asked, “Instagram?”

“Hell no,” Tom said. “I’m 56 years old for Christ’s sake. I just want to…see something.”

“We can make you a ghost account with a blank profile,” Travis suggested, trying to be helpful.

“Here, just use mine,” Zander said, pulling the laptop to him and logging in.

“Thank you,” Tom sighed, relieved.

A few seconds later, Jacqueline Durran’s full profile appeared on the screen.

“Who is this!?” Zander said, then gave a low whistle. It got the other cowboys attention. They gathered behind Zander to see for themselves.

“Tom you rascal! Are you creeping on a woman?” Hunter teased.

“No!” Tom tried, unsuccessfully, to snatch the laptop back.

Zander scrolled through her feed while the others looked on. Jackie running a Charity 5K. Jackie at a Cowboys game with and tagging Austin Durran. Jackie in what appeared to be a birthday celebration picture, surrounded by friends and family, holding a cute, chubby baby boy wearing a birthday hat. The Dallas Society Women’s luncheon pic was further down the feed, as were several check-ins tagging Alyssa Durran.

“Who’s the fine-looking lady Tom?” Luke asked.

“None of y’alls business!” Tom snapped. He wanted to look at the pictures, alone.

Juan the ranch cook left the cornbread skillet soaking in the sink and came over for a look. “Ella es muy bonita,” he said approvingly.

“When do we get to meet her?” Jake jostled.

“Never!” Tom snatched the laptop.

“Come on Tom,” Hunter taunted, “spill the tea…”

Tom surveyed their dumb, smiling faces, which varied from genuine curiosity to knowing grins. He let out a long exhale. “She is someone I knew a long time ago. I haven’t seen her since high school. 40 years. I was just curious where she is these days.”

“What prompted the curiosity?” Luke asked.

“Her father passed,” Tom said, pulling out a chair and taking a seat among the cowboys at the table. “Les, Post, and Chauncey went to pay their respects to the family at the wake tonight.”

“Why didn’t you go with?” Jake wondered.

“Let’s just say, Roger Lawry wasn’t my biggest fan back in the day.” Tom paused, running his worn hand down his silver beard thoughtfully.

“His funeral is tomorrow in Mountain Town.”

“And she’ll be there,” Travis motioned to the laptop.

“Yup,” Tom confirmed.

“Well, ding dong the bastard is dead!” Hunter slammed his hand on the table, making everyone jump.

“Now’s your chance!” Ryan urged him.

“Nooooo,” Tom shook his head defiantly. He accepted a beer from Luke, who’d retrieved a six-pack from the refrigerator and was distributing them around the table for what was quickly becoming a cowboy intervention.

“First, she was born a Lawry, which means ‘Durran’ is her married name. Those younger Durrans tagged in the photos are probably their children.”

“Are kids a deal breaker?” Luke asked.

“Not at all,” Tom said, “But a husband is.”

“I don’t see no husband in them pictures,” Ryan said as he popped the top of his beer.

“All I’m saying is it looks like she had a full and happy life in the city. Jackie has always been way out of my league. Judging by those pictures she still is,” Tom said wistfully.

“You’ll never know unless you go to the funeral and find out,” Travis nudged him, “She’ll always be the one who got away.”

“You think so?” The more Tom thought about Jackie, the more driven he felt to see her again. Maybe it would provide the closure he needed? 39 years too late, Tom thought.

“But you can’t go looking like that.” Ryan waved his hand around Tom’s face.

“Like what?!” Tom asked, offended. He strained to remember the last time he looked in a mirror.

“Yeah Tom, you’ve got to shave that shit,” Hunter pointed to his thick silver beard and mustache.

“Do you even own non-work clothes?” Zander asked.

“Ain’t got a reason to own non-work clothes,” Tom huffed. “I never leave the ranch.”

The cowboys groaned in unison.

By noon the next day, Tom had washed his truck, visited the barbershop for a shave and a haircut, shopped at the feed store for new blue jeans and a western dress shirt, and brought Luke's black suit jacket to the dry cleaner to have everything pressed and ready. His fancy boots and belt buckle were polished. He pulled his silver belly Stetson cowboy hat out of storage for the occasion.

Hunter slow clapped when Tom walked out of the bunkhouse bathroom tall, clean cut, handsomely dressed.

“You don’t look a day over 100,” Ryan teased, soliciting a smile from Tom.

Tom walked up the steps of the three-story brick gothic house that served as Mountain Town’s funeral home. He tried to blend into the steady stream of townsfolk attending the service, but his nerves, coupled with the new look and uncomfortable clothes, made him stand out like a sore thumb. Bouquets filled the ceremonial room and spilled into the reception area. Tom took off his cowboy hat and held it in his lap before taking a seat in the last row of the room. He stretched tall in his chair and discreetly scanned the crowd of attendees. He recognized a few family members sitting in the front row, but Jackie wasn’t among them.

Right before the service began, Jacqueline Durran rolled her mother’s wheelchair down the aisle towards the casket. Light shined through the stained glass windows, casting glints of color onto the aisle. Tom’s chest heaved with a heaviness he had not felt since the day Mrs. Lawry shut the door in his face and told him that Jackie was gone. He absentmindedly brought his hand to his chest to ease the pain, and let out an audible sigh.

The eulogy was generic. Tom assumed that’s because most people in attendance were there for the same reason Les dragged Port to the wake. Their memories of Roger were of a good lender and fair businessman, not a friend.

Tom’s eyes stayed glued to Jackie through the entire service. Even she remained stoic, aside from the occasional pat on her aging mother’s hand or knee.

When it was over, Tom did his best to blend back into the crowd exiting the funeral home, instead of approaching the family to offer condolences. He followed the procession to Mountain Town Cemetery. It was a warm, 80 degree April day. He stayed in his truck, window ajar and watched people gather under a sun tent at the gravesite. He’d already decided that he would not join them.

Tom simply wanted to see Jackie one last time; mission accomplished IT had not produced the closure he’d hoped for, but who was he kidding? In 1986, he knew he could love no one like he loved Jackie. That wouldn’t change if he saw her another hundred times.

He must have been staring out at the cemetery for some time because the last vehicles were pulling around him to leave. Tom started the truck to follow, but before he could shift into drive, he heard her familiar voice.

“Tom Saunders?”

Tom turned and looked directly into Jacqueline Lawry, now Durran’s, lavender gray eyes.

IV.

For the life of him, Tom could not make words come out of his mouth. He just stared at her, mouth agape. ‘Tell her she’s crossed your mind [let her know you’ve thought about her]’, ‘’Tell her she looks great,’ ‘Approach her slow and easy, like you’re dealing with a skittish mare’ Tom racked his brain to recall the ‘boys advice how to approach a woman you're interested in.

She smiled and stepped to his open window.

“Jackie,” he said her name like it was a holy word.

“You left the funeral home before I said hello. I rushed over here before you got away again.”

“I’m sorry you lost your dad.” Tom said. Roger Lawry could go to Hell as far as he was concerned, but Tom had lost both of his parents and knew the ache of losing a piece of one’s past all too well.

“Thank you,” Jackie sighed. “Mom has dementia, and I’m not sure she understands he’s gone.”

“It’s tough to watch her health fail, I’m sure,” Tom said to keep Jackie talking. Tom thought hell had a special place for Mrs. Lawry too, but the fact she couldn’t remember what a bitch she’d been to him made him slightly sympathetic.

“I moved her to a memory care facility in Mountain Town last year. Dad couldn’t care for her at the house anymore. They had in-home help but with his cancer…” Jackie’s voice trailed off.

“Anyway, you look well Tom,” she said. “It’s been…”

“Thirty-nine years,” Tom finished her sentence. “But who's counting?” He laughed.

“You look exactly the same,” he said, appreciating her.

“Aside from these stress lines on my forehead?” She pointed to her porcelain skin.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Tom said, and meant it.

A moment of awkward silence passed. Jackie broke it saying, “I have to take mom back to the care facility, but I’ll be in Mountain Town for a while getting my folks' house in order. Do you want to catch up over coffee?”

“I’d like that.”

“How about tomorrow morning? 10 a.m. at my folks'?”

“Sounds perfect.”

“You remember where it is?” She asked tentatively.

Tom nodded, like he would ever forget. “I’ll be there.”

“See you then.” Jackie patted the side of the truck and stepped back. She gave a little wave as he started the engine and drove away.

V.

Tom barely slept. The ‘boys jostled him about his snoring in the bunkhouse; at least it drowned out theirs. He forced himself to stay in bed until 4 a.m., then quietly pulled on his boots and crept out of the bunkhouse, careful to not wake the other cowboys on their day off. He did busy work, dropping a fresh round bale in the pasture and checking on the new calves. Since he had the tractor hooked up, he dragged the outdoor arena dirt.

It was Jake’s weekend to muck horse stalls, but he did eleven of them before Jake showed up at 8 a.m. They finished the rest and added a dusting of sawdust by 9. Tom had successfully distracted himself with just enough time to shower, change, and drive to Jackie’s for their coffee date.

The Lawry’s home was a stately, three story Spanish colonial stucco house on the golf course. Aside from a fresh coat of paint, it had changed little. Mr. Lawry employed a gardener, and the lawn was always immaculate. The Texas Mountain Laurel in the front yard, a sapling when he came here as a boy, had grown to its full 15 foot height. It was heavy with deep purple blooms. He stopped mid-sidewalk to inhale the fruity scent.

When he looked up, Jackie was standing in the open door. His pulse quickened. She wore jeans and a plain white v-neck t-shirt, revealing a slim gold chain with three gold heart charms around her neck. Her hair was pulled back in a nub of a ponytail. She had on a hint of make-up. Her feet were bare; it felt oddly intimate to see her red toenails. Tom forced himself to look away.

“I think I got here in a time machine,” Tom said as he approached her, both about the house, their meeting there, and her youthful appearance.

“My back doesn’t think so. I was moving boxes in dad’s office all night. He retired from the bank 13 years ago but I think he held onto every file. I’m feeling it this morning.” She placed her hand on the small of her back for effect.

“Plan to put it on the market?” Tom asked as he followed her inside. He remembered the high ceilings with exposed beams. The Spanish tile, white-washed walls, and artful iron bannisters were timeless, but the furniture was updated since Tom saw it last.

“I haven’t decided if I’m selling yet.” Jackie led Tom through the kitchen’s French doors onto the back patio where she’d set up a coffee service.

“Because your mom might come back home?”

“No chance. Mom’s dementia is so severe, she hardly knows who I am.”

“Dad laid a heavy guilt trip on me when I moved her there. He thought I should move back to Mountain Town. Take up residence in my old bedroom and take care of her.”

Tom scoffed. That sounded just like something the selfish, old bastard would push on his only daughter.

“It took a few weeks for her to get her bearings, but mom loves it there. She’s always been quite the socialite,” Jackie smiled at the image of her mother mingling in the dayroom. “I’m resisting putting it on the market because, well, I’ve always loved this house, and Mountain Town. Now that my kids are grown, there’s no really no reason to stay in Dallas.” She shrugged, then as a side note added, “Their dad and I divorced 9 years ago…”

The information made Tom’s heart skip a beat. Jackie poured Tom a cup of coffee. He declined cream of sugar. Then poured one for herself and added both.

“Tell me about your kids?” Tom prompted.

Jackie’s face lit up. Clearly, they were her pride and joy. “The youngest is an M.B.A. student at UT Dallas, studying finance. He was on the golf team all four years as an undergraduate. Now he spends all his spare time on the greens.”

“My middle daughter studied retail management in school. She manages a boutique downtown.”

“My oldest son lives south of Dallas. After the Army, he moved to Milford to work for a metal fabrication company.”

“Welding?” Tom perked up. Les had taught him to weld when he first came to the Bar C. He was no professional, but he could fix just about any fence, pen, or machinery problem on the ranch.

“Welding, cutting, assembling, repairing… he does it all. The shop he works for does all sorts of projects for construction firms, manufacturers, oil and energy companies.”

“Wow,” Tom said. Jackie smirked, somehow knowing that would impress him more than her other children’s degrees and business acumen.

“He’s incredibly talented. Does a lot of custom work out of his home shop. He’s always wanted to do his own thing full-time, but he’s had a rough couple of years. His wife had a rare blood disorder. She passed giving birth to Branson.”

Tom remembered the picture of Jackie holding the young boy, Branson, her grandchild. “That’s horrible.”

Jackie nodded. “We help as much as he lets us, but he’s…well, proud is an understatement,” she chuckled.

“Anyway,” Jackie jolted back to the moment. “What about you? What have you been doing for the last 4 decades?” Her tone turned light. “Traded the hardhat for a cowboy hat?”

She remembered the hardhat he wore to the quarry, hanging on a hook in his truck back in the day.

“I actually traded hats right after you left. I never went to work for the quarry full time after high school. I tried breaking horses on a whim. Turned out I was pretty good at it. I went on the rodeo circuit, riding broncs for eight years.”

“I heard that, but it sounded so unlike you I thought it was a rumor,” Jackie admitted.

Tom wondered if her mother had passed information from the Mountain Town gossip mill or if Jackie had another source in town.

“How’d you end up back in Mountain Town after eight years on the road?” She asked.

“Busted leg.”

Jackie cringed.

“It was as bad as it sounds,” Tom chuckled, “But fortunately, doc fixed me up with an iron rod and a few pins.” He ran his index finger down his femur and poked at his knee to illustrate. “But I developed a fondness for horses, livestock, and ranching. I came home and went to work for Les Calder.”

“The Bar C,” Jackie said with recognition. Everybody with a connection to Mountain Town knew the Bar C Ranch. “How are the Calders?”

“Les’s wife Carla passed away a few years back. Les retired and Post took the reins. I served as trail boss under both.” Tom was proud of the affiliation with the ranch and its people.

“Wife? Kids?” she asked. Though Tom had elected to live in the bunkhouse with the other cowboys, the trail boss typically lived in a private residence on the property with his family. It was a perk of the job that Tom never took Les up on.

“Neither,” Tom told her. Jackie fidgeted nervously. Tom assumed she felt bad for gushing about her family, when he didn’t have any, so he smiled and added, “But the Calders and Bar C cowboys are as close to kin as it gets.”

After two refills and an enormous breakfast pastry, the conversation lagged. Tom waited a beat before asking, “What really happened when you left Mountain Town, Jackie?”

Jackie turned her empty mug in her hands.

“You don’t have to tell me if you don’t feel comfortable.” Tom balanced his cowboy hat on his knee and ran a hand through his cropped gray hair, smoothing it to the side. “I came to the funeral yesterday because I needed to see you again- to know you are okay. I spent a lot of years worrying you weren’t.”

Jackie looked away, swiping tears from her cheeks.

“I tried calling, coming by the house. I confronted your dad and mom. They told me you were gone. Told me to forget about you-the baby was gone and you weren’t coming back.”

“I knew you would try, Tom,” Jackie’s watery eyes met his.

“I had a lot of time to think while I was on the rodeo circuit. I thought about the way I reacted when you told me, assuming I knew what you wanted. Hindsight is 20/20, I guess. Maybe we would have had a chance if I’d have asked what you wanted instead of trying to decide for you. I was no better than your folks during that hard time. I’m sorry.”

“Oh Tom. You have nothing to be sorry about,” she said sternly. “But I do...” Tom waved off her concern, but Jackie insisted “I do Tom, I had him.”

To be continued…

Listen to Tom on the Mountain Town Podcast